On a cold December day in 1955, forty-two year old Rosa Parks got on a bus in Montgomery, illness Alabama and challenged the existing laws in America. As the white section on the racially segregated bus filled up, she refused to give up her seat to a white passenger. Rosa Parks became the voice of a movement.

Perhaps the world sees a hint of Rosa Parks in Zunera Ishaq’s defiance of Canadian law. Zunera, a 29-year-old Pakistani Sunni Muslim woman is at the centre of a maelstrom for refusing to remove her niqab during the Canadian citizenship swearing-in ceremony. Zunera’s resistance is seen as addressing larger issues of freedom, equality and respect for diversity. Her case has resulted in a federal judge striking down the ban on the niqab during the citizenship ceremony.

Zunera has polarized public opinion. It is unfortunate that issues pertaining to women have become entwined somehow with terrorism. For away from the heightened rhetoric of terrorism, these issues might have been viewed dispassionately and with far greater insight. On the one hand is the matter of personal choice; it seems incredible that a government can dictate what we, as individuals, choose to wear. Surely that is an infringement of our human rights?

And yet every conversation we have about freedom and equality must mean exactly that – an advancement of these rights. It must make life for underprivileged and disenfranchised people that much better. How does Zunera’s position on the niqab advance the cause of gender equality? How does it address the concerns of women for whom gender inequality subjects them to inhumane conditions of living?

Zunera insists her preference for the niqab is not based solely on religious obligation but informed choice. She is quoted as saying, “I like how it makes me feel: like people have to look beyond what I look like to get to know me. That I don’t have to worry about my physical appearance and can concentrate on my inner self. That it empowers me in this regard.”

Zunera has underestimated the complexity of human relationships and people’s ability to navigate them. Is clothing really an impediment to getting to know people? At any given moment, human beings will exhibit a plethora of emotions: lust, greed, humility, want, desire, wit, cunning, pain, joy. What does it mean when women believe that without the subterfuge of clothing, people are incapable of deciphering emotion? Such a ruse unfortunately has become staple diet for liberals including stout-hearted bra-burning feminists. Today, the same brand of liberals has turned mealy-mouthed apologist trying to reclaim the burka and niqab as some sort of symbol of emancipation, as if Saudi Arabia’s and the Taliban’s strictures for women’s attire were something other than veiled misogyny.

Yes, Zunera has a right to wear whatever she wants. But no, the burka is not a symbol of anyone’s freedom.

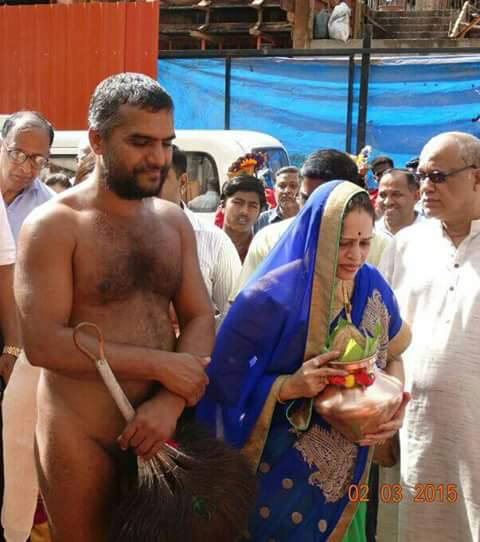

Digamber Kamat greeting Digamber Jain aesthetic

The politics of clothing and its inherent paradox can be highlighted by an incident which occurred in Goa this week. Photographs emerged of the former chief minister of Goa, Digamber Kamat, walking in plain sight with a man who was stark naked. Reactions to the photos ranged from disbelief to condemnation and ridicule. But remorse immediately set in when the public learned that the naked man was a Digamber Jain ascetic. Their renunciation of worldly pursuits requires them to travel on foot, naked and living a life of frugality.

So who do our bodies belong to? To us, to the state, to God? Nothing, it seems, is more political than the human body. In the case of Zunera, some Muslims have advised her that removing her veil is permitted. The prophet Muhammed himself had asked his wife to unveil if she accompanied him at night. The Canadian courts have upheld Zunera’s decision to keep her face veiled because the Citizenship Act allows for “the greatest possible freedom in the religious solemnization”. In the case of the Digambar Jain sadhu it becomes perfectly natural for a man to wander the streets naked, public decency be damned, if he is an avowed ascetic.

In both these justifications one thing becomes crystal clear. That religion is dictating the politics of clothing. How we interpret the right to wear what we want is determined by what we perceive to be God’s instruction. And people do this because they seek to propitiate God’s goodwill. If anything, it shows us just how fragile and vulnerable this need for propitiation is within us. And as humans we can understand that vulnerability; that desire of not wanting to displease the Almighty. And yet, rationality demands that we move beyond such narrow negotiations with morality.

The contradictions are stunning. The same feminists who decry women’s inequality fight for the right of a woman to perform the misogynistic ritual of covering her face. The same Hindu conservatives who condemn Goa’s “bikini and pub” culture suddenly have no problem when a “holy man” walks buck naked through the streets.

In the end, that which is immoral or unequal or otherwise awry doesn’t cease to be so just because it comes with a dose of religion.

Shame! Big Shame! Use ur thinking power & dnt act like animals illrational. Shame!

This is new stunt for gathering votes.I don’t understand why this literate people around.

Really crazy.

This all dirty politics

Great article. Religion should make us better humans first n last…..the rest is secondary.