Book Review

Valmiki Faleiro’s Delightful New Book Tells The Story Of Margao’s Espirito Santo Church

If you’re travelling by a hoppity scooter or car from Panjim to Margao, when you turn left at the communidade building you enter the largo de igreja (church square). For those of us without any claim to nobility, the area is simply known as the old market, beyond which lies a new market, a hodgepodge of unsightly buildings and traffic congestion which for years has had as its elected MLA, the ineffectual Digamber Kamat. The irony is, Margao today, abandoned by industrialists and even itinerant tourists, had been in centuries of yore, a bastion of political and economic power.

The rise of Margao is studiously narrated in a new book by Valmiki Faleiro entitled Soaring Spirits: 450 years of Margao’s Espirito Santo Church (publisher Goa, 1556). Brave is perhaps a strange word to use when describing a book whose primary focus is the history of a church. But in the perilous times we live in, when Christians are so easily vilified, Faleiro writes with the defiance of a matador. He does not flinch from stating that the arrival of Christianity displaced indigenous Hindu settlements. But history is, if anything, a tumultuous wave of displacement, usurpation, revolt and counter-revolt. Before the Portuguese had even arrived in Mathgram, the former name of Margao, the Maru (demon)-worshipping Mhars, the nature-loving Gonvllis, the Gawdas and the Kunbis had each made their indelible mark on the city. Each in turn subjugated previous settlers and usurped the commons. The Kunbis, for instance, established a hegemony so relentless, that every agrarian venture began with their tribal name Ku.

The uncontested dominance of tribalism was to survive until the arrival of the Indo-Aryan Saraswats, a people who exploited cattle, rode the horse and chariot into battle, and who spoke an old form of Sanskrit, proclaiming the Rig Veda. While India’s ancient history may be subject to reinterpretation as more archaeological, carbon-dating, DNA and empirical evidence is collected, Faleiro relies on trustworthy secondary sources to draw his timeline. By the 1500s, the Portuguese had arrived. The first church in Salcette, writes Faleiro, was built neither in Verna, which celebrated the first Mass, nor in Cortalim, which witnessed the first conversion to Christianity. Nor was it built in Margao, the principal village at the time. It was built as a chapel at Rachol in 1521. Numbers may have been grossly exaggerated by medieval propagandists but some 700 natives of Salcete are said to have been baptised in 1564 alone. Proselytising efforts seemed encouraging. Town criers went around villages proclaiming that those who converted will be ‘favoured and helped.’ Among the first converts was a Mangesh Shenoy who traced his ancestry to Bengal. On being baptised, he became Pero Mascarenhas.

By the turn of the 18th century, Margao had been thoroughly gentrified; the inhabitants of the largo, a curious mix of influential indigenous Goans, mestis (bi-racial) and descendentes (those who claim Portuguese ancestry). In the labyrinthine corridors of Goan history, it became increasingly difficult to discern between European and Saraswat stock. Both were relatively light-skinned and it is entirely possible that bi-racial ancestries and overlapping caste identities, particularly in the Margao area, were manufactured, just as they are to this day. The worst excesses of Margao’s gentry were parodied by Francisco Joao da Costa (of the da Costa canning family), writing in 1896 under the pseudonym Gip.

Valmiki Faleiro

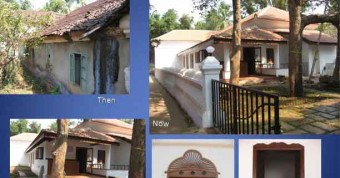

Despite its petty vanities and European affectations, Margao gave birth to republicans, parliamentarians, poets, musicians, printing presses, an indigenous clergy of the highest distinction, medical doctors, and an elite society which led the way in reformation, particularly in gender equality and education. All this has been insightfully chronicled by Faleiro, in the process revealing intriguing hidden histories. For instance, the houses were purposefully stacked together. If Margao came under attack, women and children escaped through the interconnected houses to emerge in the courtyard of the Santos Vas house.

Chardos and brahmins, save for periodic political rivalries, acted as one bloc. The people they disenfranchised, and whose histories are beyond the purview of this book, were the sudhir mundkars (tenanted labour) who lived on the periphery of the Church square. These mundkars led ruined lives until British India and East Africa presented them with opportunities. Here, they made their mark as skilled carpenters, shoe-makers and tailors and produced seminal art forms. For instance, the humble house of Pai Agostinho, the father of Goan tiatr, is just a few minutes from the church.

This richly detailed book is a pleasure to read and a wonderful contribution to our understanding of Lusitanised Goa. By providing us a glimpse into these turn-of-the-century lives, Faleiro has left a trail for cultural anthropologists to build on. He derives his authority on the subject by being a proud gaunkar (native) of Margao and a resident of the largo, having carefully gathered oral histories and genealogies over the decades. We await his next promised book, an account of Margao beyond the church square.